Introduction

India is home to a diverse array of luxurious lime plaster traditions. From the desert state of Rajasthan in the north to the tropical monsoonal climate of Kerala in the south and the hot, dry climate of Tamil Nadu in the east, each region has its own unique indigenous expression reflecting the local geological and cultural context.

Master Artisans across the country have spent centuries perfecting their traditions, creating stunning finishes from abundantly available local, natural materials. Stone lime is typical in Rajasthan whilst shell limes are the norm in the southern states. Marble is the aggregate of choice for the fine Araish plasters in Rajasthan whilst white quartz is favoured in Chettinadu. Herbal admixtures are used across all regions to impart favourable characteristics. However the specific admixture preferred varies according to local availability.

This article will give a brief outline of three unique traditions of India. Firstly the finishes practiced in Shekawati – Rajasthan, followed by the lime plasters used for mural making in Kerala and finally the luxurious Chettinadu plaster of Tamil Nadu. This is by no means an exhaustive exploration of all Indian lime plaster traditions. More on other traditions will come in another post soon.

Rajasthani Lime Plasters – Shekawati

Rajasthan is well known in India for the lime plasters that grace the walls of some of the countries most elaborate royal palaces and sumptuous havelis. The state has extensive resources of lime of varying types and qualities. The plasters of each region across the state have evolved adapting their unique recipes and techniques according to the variety of lime available.

In the Shekawati region of Rajasthan three distinct lime plasters can be found. Thappi plaster is commonly used as a finish plaster on exterior boundary walls of Palace and Haveli compounds. In addition it is the base plaster over which the two finer plaster finishes Lohi and Araish are applied.

Thappi Plaster

Thappi plaster consists of quick lime, sand, surki (red brick powder) and herbal admixtures. Typically fermented gud (unrefined sugar) water and fermented methi (fenugreek) water are the preferred admixtures used to improve workability, water resistance, hydration of the plaster and to improve the strength of the mortar.

The plaster is applied as the base plaster to level the wall in preparation for the finer finish plasters Lohi and Araish. As the plaster dries it is tapped (given ‘Thappi’) to compress the plaster on to the wall and prevent the formation of cracks. The process of giving Thappi results in the formation of a hatched pattern across the plaster. Giving Thappi plaster a unique textured finish.

Thappi plaster must be cured for 1 month prior to the application of Lohi or Araish as finish plasters. This is crucial as the Thappi plaster may continue to develop micro cracks which is not a problem for the base plaster but is a problem for the finish plasters, where we want a perfect surface.

Interestingly the name of this plaster ‘Thappi’ is also the term used for the tool to apply the plaster on the wall as well as the action of giving ‘Thappi’ to the plaster.

Lohi Plaster

Lohi is a fine finish plaster applied over Thappi plaster. Commonly used for interior walls and floors wherever a smooth finish was preferred. Made of finely sieved quick lime and surki. Lohi does not require the addition of any herbal admixtures. However, it is ground on a stone to form a smooth paste prior to application.

Araish

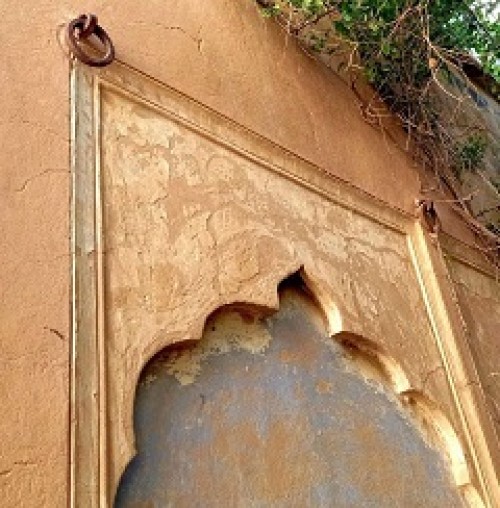

The pride of the tradition, Araish is a luxurious polished lime plaster. Araish is found adorning the walls of opulent palaces and the havelis of wealthy merchants. A pure white plaster burnished to a high sheen, it is considered the most extravagant of plasters.

Made of finely sieved quick lime mixed with white marble powder. As with Lohi, before application Araish must be ground to a smooth paste before application.

Application is a slow process as the fine plaster is gradually built up in minute layers. As the plaster begins to dry it is burnished with a hard stone to achieve a mirror like finish. The end result being a silky smooth plaster, irresistible to touch. India’s own version of Tadelakt, the famous polished plaster of Morocco.

Shekawati is famous for the elaborate frescoes that adorn many of the havelis. Araish is the base upon which the frescoes were painted. Natural stone pigments were applied over the wet Araish plaster. Artists would have to complete their artworks before the plaster set, allowing for the final burnishing to take place, compressing the pigments within the lime plaster and creating artworks able to last generations.

To learn how to create these unique finishes for yourself, join us for one of our Rajasthani Lime Plaster Workshops and learn directly from master artisans who have been practicing this tradition for generations.

Kerala – Lime Plasters for Murals

The state of Kerala in the south of India experiences a tropical climate with a long coastline. Not surprisingly their lime plaster tradition incorporates a range of ingredients particular to the context. These lime plasters serve as the base for Kerala Murals.

Shell lime is the most abundant form of lime available. Burnt in traditional kilns, it is recognised as one of the most pure forms of lime. Used in its slaked form, it is mixed with sand for the base layer along with herbal admixtures, Kuddukai (Terminalia Chebula) and or jaggery water. The addition of which promotes a faster curing time and stronger set. This layer is allowed to cure for one week before the second layer of plaster is applied. Preferably the sand and lime are mixed together and left for a week before use. The herbal admixtures are added just prior to application.

For the second layer lime and sand is used once again, this time with the addition of cotton fibre. Prior to application the plaster mixture is ground on a stone to improve workability whilst adding strength to the finished plaster.

The final layer of plaster that is applied just prior to beginning the mural consists of finely sieved slaked lime mixed with tender coconut water. This is then applied in 25 – 30 thin layers, alternating vertically then horizontally.

Kerala is home to a thriving mural tradition. This was however not always the case. Despite a long history of patronage for the arts by royalty, wealthy merchants, temples, churches and mosques there was a period post independence that saw support for these arts withdrawn. Ultimately this resulted in the near loss of Kerala Murals as a living tradition. Thankfully the tradition was revived in the 1980s with the establishment of the Guruvayur Institute of Mural Painting.

If you would like to learn about this tradition in detail considering joining us for one of our Kerala Mural Workshops

Tamil Nadu – Chettinad Plaster

Chettinad plaster is found gracing the walls of many grand homes of the wealthy Chettiyar trader, financier community who call the city of Chettinad home. Many of the original Chettinad plasters, some now more than a century old, exhibit a shine so radiant one can see one’s own reflection in them.

Most famous for the use of egg whites to achieve the water resistant, mirror finish, the creation of this fine finish plaster involves an elaborate process of up to six layers of plaster.

Shell lime is the traditional form of lime that is used in Tamil Nadu. The quality of the lime is of great importance. Aged, thoroughly slaked lime was crucial. There are stories of lime aged for 12 years, and of aged lime being given as wedding gifts, so precious was this commodity,

For the first layer of plaster slaked lime and coarse sharp river sand are combined and kept for a minimum of seven days to soften. Prior to application the plaster is beaten with a wooden pole to achieve a sticky consistency. Once achieved herbal admixtures – fermented Kuddukai and jaggery water are added. The addition of these admixtures improves binding and initiates setting. This layer is used to level the wall in preparation for the finer layers.

The second layer through to the second last (4th or 5th layer) involves the combination of slaked lime with sieved pure white quartz powder of increasingly finer grades and increasingly thin layers. As with the first layer the lime and quartz are combined and kept for a minimum of two days to improve cohesion and binding. Just prior to application the plaster is beaten and herbal admixtures added.

The final sixth layer of plaster consists of finely sieved slaked lime and finest sieved quartz powder. Just prior to application a mixture of egg white and curd water are added to the plaster. It is the application of these that is credited with the brilliant shine and water proof finish.

Once the final layer achieves a leather hard set the wall is burnished using either a marble or quartz stone. Granite is avoided as it is considered a hot stone that will give heat to the plaster. Marble and quartz are considered cool stones that will not give heat.

In direct contrast to Rajasthani plasters, Chettinad plasters are achieved wet on wet. Meaning each of the consecutive layers of plaster is ideally applied over the plaster beneath whilst it is still wet. Ideally all six layers of plaster should be applied within two days. The first three layers on the first day and the final three layers on the second.

Both the application process and preparation of materials is a laborious and time intensive process. The pounding of white quartz stone to an increasingly fine grade takes time. That is precisely why this fine finish plaster is generally only found in the most luxurious of homes.

More rustic versions of this plaster can be found in more humble homes. However they tend to be an off white colour, reflecting the use of river sand instead of pure white quartz stone. Thereby reducing the labour required to prepare the required materials.

Intangible Heritage Loss

In all of these traditions just a handful of master artisans remain who carry with them the knowledge of their forefathers on how to create these luxurious finishes. Some guard this knowledge as their family secret. Others recognise the importance of keeping these traditions alive and are happy to share the wisdom of their ancestors with curious learners.